(Please note that I originally wrote this essay for E-International Relations, and I have republished it here on a Creative Commons licence. If you wish to republish this piece, please respect E-IR's republishing guidelines)

In Kim Stanley Robinson’s epic 1993 sci-fi novel Red Mars, a pioneering group of scientists establish a colony on Mars. Some imagine it as a chance for a new life, run on entirely different principles from the chaotic Earth. Over time, though, the illusion is shattered as multinational corporations operating under the banner of governments move in, viewing Mars as nothing but an extension to business-as-usual.

It is a story that undoubtedly resonates with some members of the Bitcoin community. The vision of a free-floating digital cryptocurrency economy, divorced from the politics of colossal banks and aggressive governments, is under threat. Take, for example, the purists at Dark Wallet, accusing the Bitcoin Foundation of selling out to the regulators and the likes of the Winklevoss Twins.

Bitcoin sometimes appears akin to an illegal immigrant, trying to decide whether to seek out a rebellious existence in the black-market economy, or whether to don the slick clothes of the Silicon Valley establishment. The latter position – involving publicly accepting regulation and tax whilst privately lobbying against it – is obviously more acceptable and familiar to authorities.

Of course, any new scene is prone to developing internal echo chambers that amplify both commonalities and differences. While questions regarding Bitcoin’s regulatory status lead hyped-up cryptocurrency evangelists to engage in intense sectarian debates, to many onlookers Bitcoin is just a passing curiosity, a damp squib that will eventually suffer an ignoble death by media boredom. It is a mistake to believe that, though. The core innovation of Bitcoin is not going away, and it is deeper than currency.

What has been introduced to the world is a method to create decentralised peer-validated time-stamped ledgers. That is a fancy way of saying it is a method for bypassing the use of centralised officials in recording stuff. Such officials are pervasive in society, from a bank that records electronic transactions between me and my landlord, to patent officers that record the date of new innovations, to parliamentary registers noting the passing of new legislative acts.

The most visible use of this technical accomplishment is in the realm of currency, though, so it is worth briefly explaining the basics of Bitcoin in order to understand the political visions being unleashed as a result of it.

The technical vision 1.0

Banks are information intermediaries. Gone are the days of the merchant dumping a hoard of physical gold into the vaults for safekeeping. Nowadays, if you have ‘£350 in the bank’, it merely means the bank has recorded that for you in their data centre, on a database that has your account number and a corresponding entry saying ‘350’ next to it. If you want to pay someone electronically, you essentially send a message to your bank, identifying yourself via a pin or card number, asking them to change that entry in their database and to inform the recipient’s bank to do the same with the recipient’s account.

Thus, commercial banks collectively act as a cartel controlling the recording of transaction data, and it is via this process that they keep score of ‘how much money’ we have. To create a secure electronic currency system that does not rely on these banks thus requires three interacting elements. Firstly, one needs to replace the private databases that are controlled by them. Secondly, one needs to provide a way for people to change the information on that database (‘move money around’). Thirdly, one needs to convince people that the units being moved around are worth something.

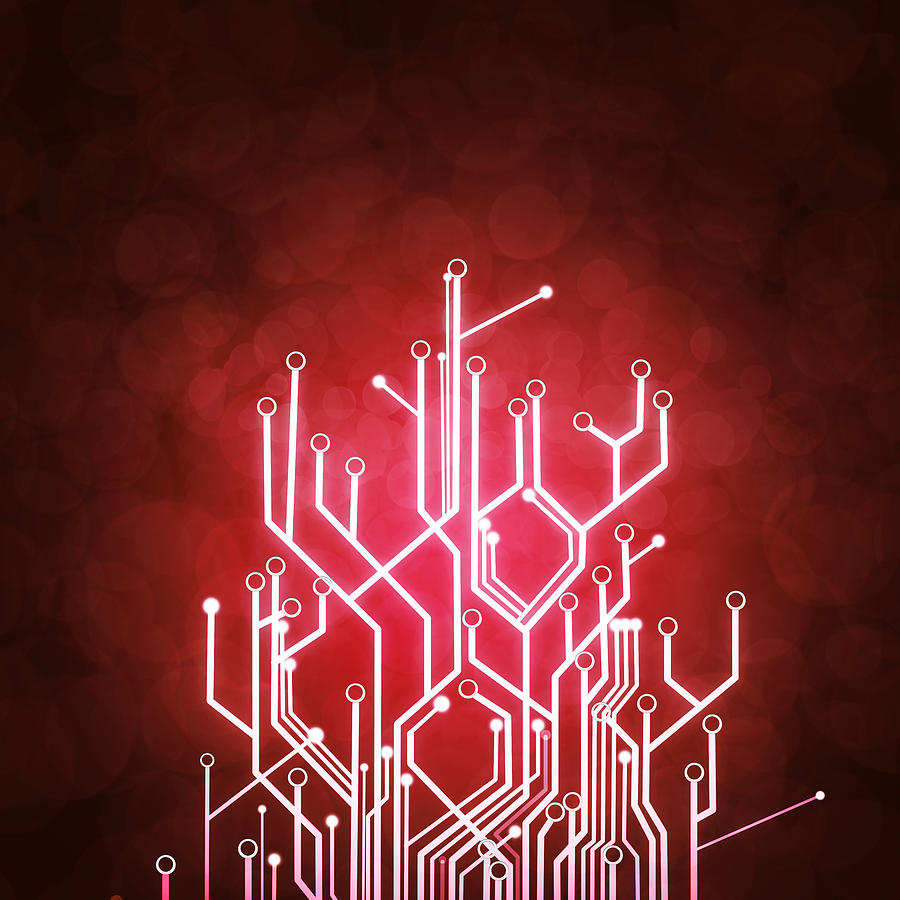

To solve the first element, Bitcoin provides a public database, or ledger, that is referred to reverently as the blockchain. There is a way for people to submit information for recording in the ledger, but once it gets recorded, it cannot be edited in hindsight. If you’ve heard about bitcoin ‘mining’ (using ‘hashing algorithms’), that is what that is all about. A scattered collective of mercenary clerks essentially hire their computers out to collectively maintain the ledger, baking (or weaving) transaction records into it.

Secondly, Bitcoin has a process for individuals to identify themselves in order to submit transactions to those clerks to be recorded on that ledger. That is where public-key cryptography comes in. I have a public Bitcoin address (somewhat akin to my account number at a bank) and I then control that public address with a private key (a bit like I use my private pin number to associate myself with my bank account). This is what provides anonymity.

The result of these two elements, when put together, is the ability for anonymous individuals to record transactions between their bitcoin accounts on a database that is held and secured by a decentralised network of techno-clerks (‘miners’). As for the third element – convincing people that the units being transacted are worth something – that is a more subtle question entirely that I will not address here.

The political vision 1.0

Note the immediate political implications. Within the Bitcoin system, a set of powerful central intermediaries (the cartel of commercial banks, connected together via the central bank, underwritten by government), gets replaced with a more diffuse network intermediary, apparently controlled by no-one in particular.

This generally appeals to people who wish to devolve power away from banks by introducing more diversity into the monetary system. Those with a left-wing anarchist bent, who perceive the state and banking sector as representing the same elite interests, may recognise in it the potential for collective direct democratic governance of currency. It has really appealed, though, to conservative libertarians who perceive it as a commodity-like currency, free from the evils of the central bank and regulation.

The corresponding political reaction from policy-makers and establishment types takes three immediate forms. Firstly, there are concerns about it being used for money laundering and crime (‘Bitcoin is the dark side’). Secondly, there are concerns about consumer protection (‘Bitcoin is full of cowboy operators’). Thirdly, there are concerns about tax (‘this allows people to evade tax’).

The general status quo bias of regulators, who fixate on the negative potentials of Bitcoin whilst remaining blind to negatives in the current system, sets the stage for a political battle. Bitcoin enthusiasts, passionate about protecting the niche they have carved out, become prone to imagining conspiratorial scenes of threatened banks fretfully lobbying the government to ban Bitcoin, or of paranoid politicians panicking about the integrity of the national currency.

The technical vision 2.0

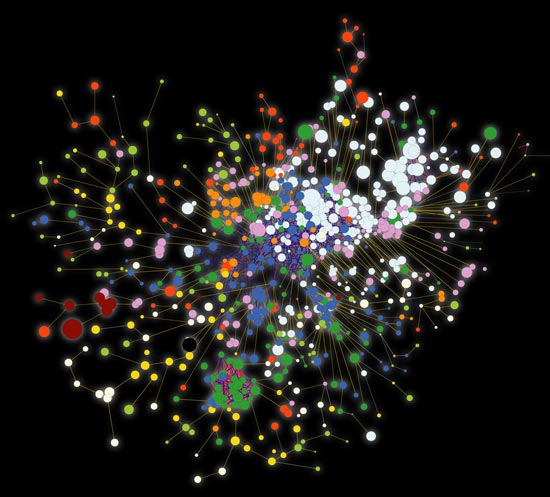

Outside the media hype around these Bitcoin dramas, though, a deeper movement is developing. It focuses not only on Bitcoin’s potential to disrupt commercial banks, but also on the more general potential for decentralised blockchains to disrupt other types of centralised information intermediaries.

Copyright authorities, for example, record people’s claims to having produced a unique work at a unique date and authoritatively stamp it for them. Such centralised ‘timestamping’ more generally is called ‘notarisation’. One non-monetary function for a Bitcoin-style blockchain could thus be to replace the privately controlled ledger of the notary with a public ledger that people can record claims on. This is precisely what Proof of Existence and Originstamp are working on.

And what about domain name system (DNS) registries that record web addresses? When you type in a URL like www.e-ir.info, the browser first steers you to aDNS registry like Afilias, which maintains a private database of URLs alongside information on which IP address to send you to. One can, however, use a blockchain to create a decentralised registry of domain name ownership, which is what Namecoin is doing. Theoretically, this process could be used to record share ownership, land ownership, or ownership in general (see, for example, Mastercoin’s projects).

The biggest information intermediaries, though, are often hidden in plain sight. What is Facebook? Isn’t it just a company that you send information to, which is then stored in their database and subsequently displayed to you and your friends? You log in with your password (proving your identity), and then can alter that database by sending them further messages (‘I’d like to delete that photo’). Likewise with Twitter, Dropbox, and countless other web services.

But what if you could create interactive web services that did not revolve around single information intermediaries like Facebook? That is precisely what groups like Ethereum are working towards. Where Bitcoin is a way to record simple transaction information on a decentralised ledger, Ethereum wants to create a ‘decentralised computational engine’. This is a system for running programmes, or executing contracts, on a blockchain held in play via a distributed network of computers rather than Mark Zuckerberg’s data centres.

It all starts to sounds quite sci-fi, but organisations like Ethereum are leading the charge on building ‘Decentralised Autonomous Organisations’, hardcoded entities that people can interact with, but that nobody in particular controls. I send information to this entity, triggering the code and setting in motion further actions. As Bitshares describes it, such an organisation “has a business plan encoded in open source software that executes automatically in an entirely transparent and trustworthy manner.”

The political vision 2.0

By removing a central point of control, decentralised systems based on code – whether they exist to move Bitcoin tokens around, store files, or build contracts – resemble self-contained robots. Mark Zuckerberg of Facebook or Jamie Dimon of JP Morgan Chase are human faces behind the digital interface of the services they run. They can overtly manipulate, or bow in to pressure to censor. A decentralised currency or a decentralised version of Twitter seems immune from such manipulation.

It is this that gives rise to a narrative of empowerment and, indeed, at first sight this offers an exhilarating vision of self-contained outposts of freedom within a world otherwise dominated by large corruptible institutions. At many cryptocurrency meet-ups, there is an excitable mix of techno-babble infused with social claims. The blockchain can record contracts between free individuals, and if enforcement mechanisms can be coded in to create self-enforcing ‘smart contracts’, we have a system for building encoded law that bypasses states.

Bitcoin and other blockchain technologies, though, are empowering right now precisely because they are underdogs. They introduce diversity into the existing system and thereby expand our range of tools. In the minds of hardcore proponents, though, blockchain technologies are more than this. They are a replacement system, superior to existing institutions in every possible way. When amplified to this extreme, though, the apparently utopian project can begin to take on a dystopian, conservative hue.

Binary politics

When asked about why Bitcoin is superior to other currencies, proponents often point to its ‘trustless‘ nature. No trust needs be placed in fallible ‘governments and corporations’. Rather, a self-sustaining system can be created by individuals following a set of rules that are set apart from human frailties or intervention. Such a system is assumed to be fairer by allowing people to win out against those powers who can abuse rules.

The vision thus is not one of bands of people getting together into mutualistic self-help groups. Rather, it is one of individuals acting as autonomous agents, operating via the hardcoded rules with other autonomous agents, thereby avoiding those who seek to harm their interests.

Note the underlying dim view of human nature. While anarchist philosophers often imagine alternative governance systems based on mutualistic community foundations, the ‘empowerment’ here does not stem from building community ties. Rather it is imagined to come from retreating from trust and taking refuge in a defensive individualism mediated via mathematical contractual law.

It carries a certain disdain for human imperfection, particularly the imperfection of those in power, but by implication the imperfection of everyone in society. We need to be protected from ourselves by vesting power in lines of code that execute automatically. If only we can lift currency away from manipulation from the Federal Reserve. If only we can lift Wikipedia away from the corruptible Wikimedia Foundation.

Activists traditionally revel in hot-blooded asymmetric battles of interest (such as that between StrikeDebt! and the banks), implicitly holding an underlying faith in the redeemability of human-run institutions. The Bitcoin community, on the other hand, often seems attracted to a detached anti-politics, one in which action is reduced to the binary options of Buy In or Buy Out of the coded alternative. It echoes consumer notions of the world, where one ‘expresses’ oneself not via debate or negotiation, but by choosing one product over another. We’re leaving Earth for Mars. Join if you want.

It all forms an odd, tense amalgam between visions of exuberant risk-taking freedom and visions of risk-averse anti-social paranoia. This ambiguity is not unique to cryptocurrency (see, for example, this excellent parody of the trustless society), but in the case of Bitcoin, it is perhaps best exemplified by the narrative offered by Cody Wilson in Dark Wallet’s crowdfunding video. “Bitcoin is what they fear it is, a way to leave… to make a choice. There’s a system approaching perfection, just in time for our disappearance, so, let there be dark”.

The myth of political ‘exit’

But where exactly is this perfect system Wilson is disappearing to?

Back in the days of roving bands of nomadic people, the political option of ‘exit’ was a reality. If a ruler was oppressive, you could actually pack up and take to the desert in a caravan. The bizarre thing about the concept of ‘exit to the internet’ is that the internet is a technology premised on massive state and corporate investment in physical infrastructure, fibre optic cables laid under seabeds, mass production of computers from low-wage workers in the East, and mass affluence in Western nations. If you are in the position to be having dreams of technological escape, you are probably not in a position to be exiting mainstream society. You are mainstream society.

Don’t get me wrong. Wilson is a subtle and interesting thinker, and it is undoubtedly unfair to suggest that he really believes that one can escape the power dynamics of the messy real world by finding salvation in a kind of internet Matrix. What he is really trying to do is to invoke one side of the crypto-anarchist mantra of ‘privacy for the weak, but transparency for the powerful’.

That is a healthy radical impulse, but the conservative element kicks in when the assumption is made that somehow privacy alone is what enables social empowerment. That is when it turns into an individualistic ‘just leave me alone’ impulse fixated with negative liberty. Despite the rugged frontier appeal of the concept, the presumption that empowerment simply means being left alone to pursue your individual interests is essentially an ideology of the already-empowered, not the vulnerable.

This is the same tension you find in the closely related cypherpunk movement. It is often pitched as a radical empowerment movement, but as Richard Boase notes, it is “a world full of acronyms and codes, impenetrable to all but the most cynical, distrustful, and political of minds.” Indeed, crypto-geekery offers nothing like an escape from power dynamics. One merely escapes to a different set of rules, not one controlled by ‘politicians’, but one in the hands of programmers and those in control of computing power.

It is only when we think in these terms that we start to see Bitcoin not as a realm ‘lacking the rules imposed by the state’, but as a realm imposing its own rules. It offers a form of protection, but guarantees nothing like ‘empowerment’ or ‘escape’.

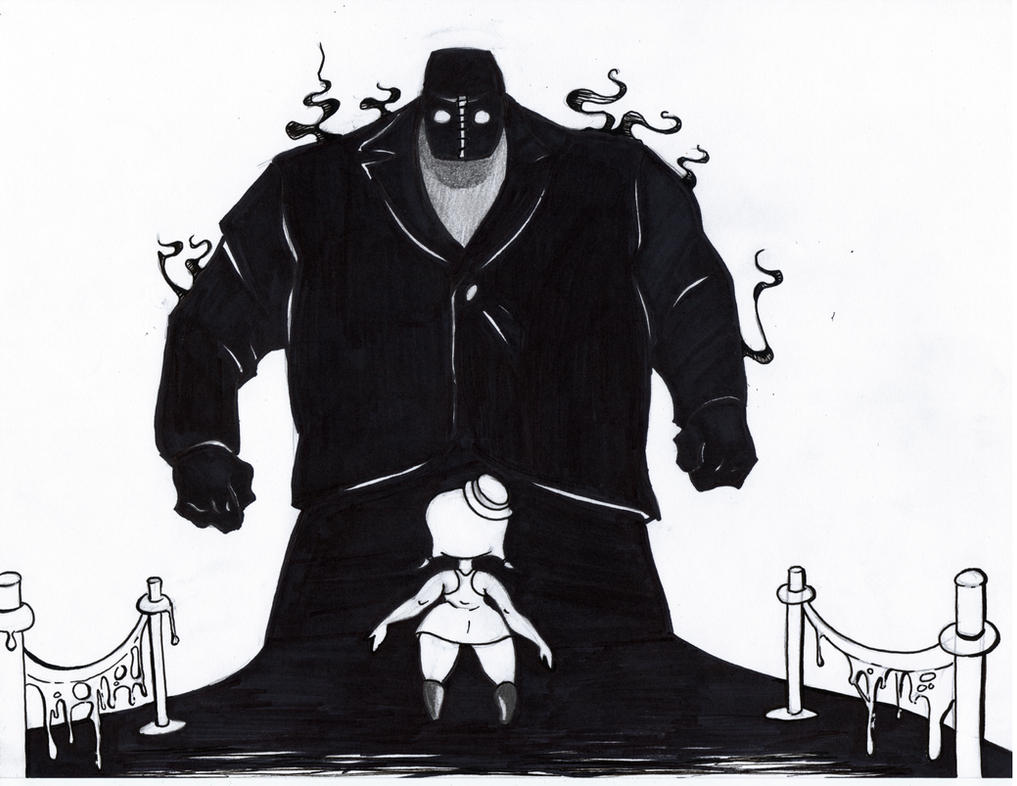

Techno-Leviathan

Technology often seems silent and inert, a world of ‘apolitical’ objects. We are thus prone to being blind to the power dynamics built into our use of it. For example, isn’t email just a useful tool? Actually, it is highly questionable whether one can ‘choose’ whether to use email or not. Sure, I can choose between Gmail or Hotmail, but email’s widespread uptake creates network effects that mean opting out becomes less of an option over time. This is where the concept of becoming ‘enslaved to technology’ emerges from. If you do not buy into it, you will be marginalised, and that is political.

This is important. While individual instances of blockchain technology can clearly be useful, as a class of technologies designed to mediate human affairs, they contain a latent potential for encouraging technocracy. When disassociated from the programmers who design them, trustless blockchains floating above human affairs contains the specter of rule by algorithms. It is a vision (probably accidently) captured by Ethereum’s Joseph Lubin when he says “There will be ways to manipulate people to make bad decisions, but there won’t be ways to manipulate the system itself”.

Interestingly, it is a similar abstraction to that made by Hobbes. In his Leviathan, self-regarding people realise that it is in their interests to exchange part of their freedom for security of self and property, and thereby enter into a contract with a Sovereign, a deified personage that sets out societal rules of engagement. The definition of this Sovereign has been softened over time – along with the fiction that you actually contract to it – but it underpins modern expectations that the government should guarantee property rights.

Conservative libertarians hold tight to the belief that, if only hard property rights and clear contracting rules are put in place, optimal systems spontaneously emerge. They are not actually that far from Hobbes in this regard, but their irritation with Hobbes’ vision is that it relies on politicians who, being actual people, do not act like a detached contractual Sovereign should, but rather attempt to meddle, make things better, or steal. Don’t decentralised blockchains offer the ultimate prospect of protected property rights with clear rules, but without the political interference?

This is essentially the vision of the internet techno-leviathan, a deified crypto-sovereign whose rules we can contract to. The rules being contracted to are a series of algorithms, step by step procedures for calculations which can only be overridden with great difficulty. Perhaps, at the outset, this represents, à la Rousseau, the general will of those who take part in the contractual network, but the key point is that if you get locked into a contract on that system, there is no breaking out of it.

This, of course, appeals to those who believe that powerful institutions operate primarily by breaching property rights and contracts. Who really believes that though? For much of modern history, the key issue with powerful institutions has not been their willingness to break contracts. It has been their willingness to use seemingly unbreakable contracts to exert power. Contracts, in essence, resemble algorithms, coded expressions of what outcomes should happen under different circumstances. On average, they are written by technocrats and, on average, they reflect the interests of elite classes.

That is why liberation movements always seek to break contracts set in place by old regimes, whether it be peasant movements refusing to honour debt contracts to landlords, or the DRC challenging legacy mining concessions held by multinational companies, or SMEs contesting the terms of swap contracts written by Barclays lawyers. Political liberation is as much about contesting contracts as it is about enforcing them.

Building the techno-political vision 3.0

The point I am trying to make is that you do not escape the world of big corporates and big government by wishing for a trustless set of technologies that collectively resemble a technocratic crypto-sovereign. Rather, you use technology as a tool within ongoing political battles, and you maintain an ongoing critical outlook towards it. The concept of the decentralised blockchain is powerful. The cold, distrustful edge of cypherpunk, though, is only empowering when it is firmly in the service of creative warm-blooded human communities situated in the physical world of dirt and grime.

Perhaps this means de-emphasising the focus on how blockchains can be used to store digital assets or property, and focusing rather on those without assets. For example, think of the potential of blockchain voting systems that groups like Restart Democracy are experimenting with. Centralised vote-counting authorities are notorious sources of political anxiety in fragile countries. What if the ledger recording the votes cast was held by a decentralised network of citizens, with voters having a means to anonymously transmit votes to be stored on a publicly viewable database?

We do not want a future society free from people we have to trust, or one in which the most we can hope for is privacy. Rather, we want a world in which technology is used to dilute the power of those systems that cause us to doubt trust relationships. Screw escaping to Mars.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider...

I sometimes spend weeks writing these articles, and don't generally get paid to do it, so if you enjoyed please consider doing one or two of the following:- Donate by buying me a virtual beer

- Donate Bitcoin (see side panel)

- Tweet: You can tweet it out here

- Share it on your Facebook wall here

- Email it to a friend from here

- Submit to Reddit

- Link to the article from your own blog so your readers can see it too

Cheers!